Archivo

New Stuff[hide]

Reportes: From The St... : Cubadisco 2...

Tienda: Cuban Music Store

Reportes: From The St... : Cubadisco 2...

Fotos: Tom Ehrlich

Staff: Kristina Lim

Musicos: Juan Formell

Musicos: Yordamis Megret Planes

Musicos: Yasser Morejón Pino

Musicos: José Luis "Changuito" Quintana...

Musicos: Dennis Nicles Cobas

Fotos: Eli Silva

Grupos: Ritmo Oriental : 1988 - Vol. IX - 30 a...

Musicos: Rafael Paseiro Monzón

Musicos: Jiovanni Cofiño Sánchez

Photos of the Day [hide]

La Última

2 New Episodes of The Clave Chronicles

John Calloway on the Bay Area Scene

Lani Milstein on Conga Santiaguera

Two great new episodes of the leading Cuban music podcast:

Tom Ehrlich's photo of John Calloway from last month's Monterey Jazz Fest

Tom Ehrlich's photo of John Calloway from last month's Monterey Jazz Fest

John Calloway on the Bay Area Scene

Lani Milstein on Conga Santiaguera

Ned Sublette on The Clave Chronicles!

An especially exciting new episode, and hopefully the first of several with the great Ned Sublette, whose combination of knowledge about Cuban, Afro-North American, and African music puts him in a class of his own. This episode focuses on folkloric music. Here's Rebecca's description:

Rebecca speaks with musician/producer/historian Ned Sublette, author of the most comprehensive history of Cuban music in English, Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo. Sublette is leading trips to Cuba through his organization, Postmambo, and in January will embark on La Ruta de los Fundamentos, a tour focusing on Afro-Cuban sacred sites in western Cuba (email postmambo@gmail.com for more info). We talk about the dense and entangled networks of Afro-Cuban religious practice and play a few fieldwork recordings from rural western Cuba.

Two New Episodes of The Clave Chronicles

Congolese Rumba & Orisha Music

In Congalese Rumba: Cuban Music Goes Back Home, Rebecca Bodenheimer interviews French historian Charlotte Grabli on the fascinating journey of African rhythms from the Congo to Cuba and back again.

Drumming and Singing for the Orishas is a great overiew of batá rhythms in both religious and popular music--from the Oru seco to Adalberto to the Bay Area's own Jesús Díaz y su QBA.

Monterey Jazz Festival, Part 4

Here's Tom Ehrlich's third of four galleries from this year's Monterey Jazz Festival.

Dancers Samara Atkins, Juliana Cressman and Molly Levy

Dancers Samara Atkins, Juliana Cressman and Molly Levy

Ami Molinelli

Ami Molinelli

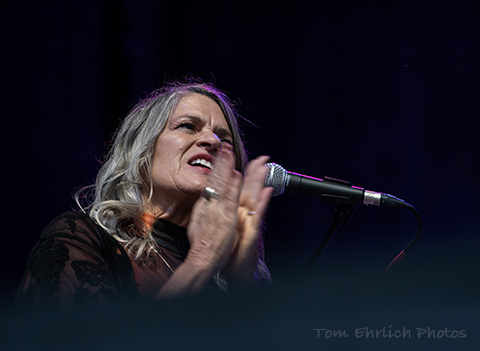

Claudia Villela

Claudia Villela

Celso Alberti

Celso Alberti

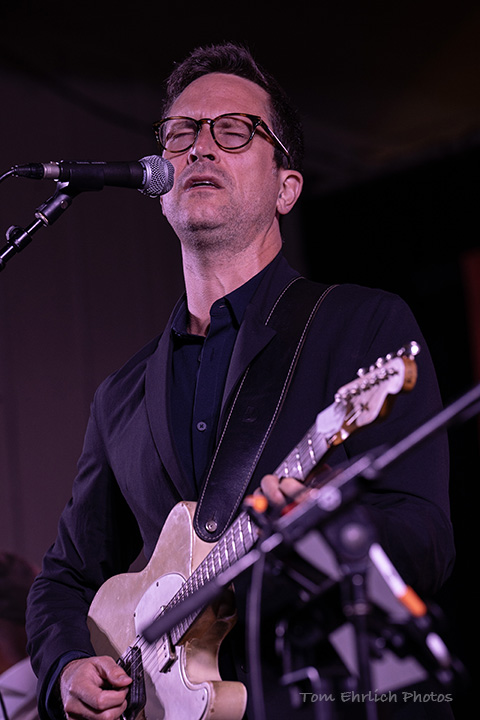

Clay Ross

Clay Ross

Falu Shah

Falu Shah

Yasushi Nakamura

Yasushi Nakamura

Clarence Penn

Clarence Penn